ERNEST MOYER'S RESEARCH

SOME PERSPECTIVES ON PYRAMID CHRONOLOGY

LIST OF SECTIONS

Great Pyramid Stone Myths

The Rock Knoll

Rate of Movement

Logistics

Lift

Course Levels

Sequence of Construction

Radio-Carbon Dates

Weather

The Khufu Cartouche

Our Lack of Knowledge

They extend some 60 to 70 miles south along the west bank of the Nile from Cairo. Over that distance forty notable structures are grouped in four major sites and several minor ones. These include Giza, with two large and seven small pyramids, eleven pyramids at Saqqara, five at Abu Sir, five at Daschur, one at Meydum, one at Abu Roash, two at Lisht, and others.

According to archeological estimates the pyramids were built over a period of about one thousand years, from approximately 2800 BC to about 1800 BC. The Table below lists all significant structures of the Old and Middle Kingdoms. This table is adapted from I. E. S. Edwards, The Pyramids of Egypt, Viking Press, New York, 1972, and from Mark Lehner, who provides a more analytical summary of pyramid construction history, with outline of shapes, exterior slopes, and volumes in his The Complete Pyramids, Thames and Hudson, London, l 997. (This last work is comprehensive and beautifully done.) This list does not include mastabas used as burial sties during the Old Kingdom, nor does it include the miniature pyramids of Merue in the Sudan. The dates are subject to considerable debate.

MAJOR PYRAMIDS OF THE OLD AND MIDDLE KINGDOMS

| Pyramid | Dynasty | Location | Base

Length in feet |

Volume

in meters3 X 105 |

| Zoser (Step Pyramid) |

3rd (c. 2686 BC) |

Saqqara | 411 E.-W. by 358 N.-S. |

3.3

|

| Sekhemkhet | 3rd | Saqqara |

395

|

Unfinished

|

| Khaba (?) | 3rd | Zawiyet el-Aryan |

276

|

Unfinished

|

| Seneferu | 4th (c. 2600 BC) |

Meydum |

473

|

3.4

|

| Bent Pyramid | 4th | Dahshur |

620

|

14.1

|

| Flat Pyramid | 4th | Dahshur |

719

|

16.9

|

| Giza 1 | 4th | Giza |

756

|

26.0

|

| Djedefre | 4th | Abu Roash |

320

|

1.3

|

| Giza 2 | 4th | Giza |

708

|

21.5

|

| Mycerinus | 4th | Giza |

356

|

2.4

|

| Nebka(?) | 4th(?) | Zawiyet el-Aryan |

Unfinished

|

|

| Userkaf | 5th (c. 2490 BC) |

Saqqara |

247

|

0.9

|

| Sahure | 5th | Abu Sir |

257

|

1.0

|

| Neferirkare | 5th | Abu Sir |

360

|

2.8

|

| Neferefre | 5th | Abu Sir |

197

|

0.5

|

| Niuserre | 5th | Abu Sir |

274

|

1.3

|

| Isesi | 5th | Saqqara |

265

|

1.1

|

| Unas | 5th | Saqqara |

220

|

0.5

|

| Teti | 6th (c. 2345 BC) |

Saqqara |

210

|

1.0

|

| Pepi I | 6th | Saqqara |

250

|

0.9

|

| Merenre | 6th | Saqqara |

263

|

1.1

|

| Pepi II | 6th | Saqqara |

258

|

1.0

|

| Ibi | 8th (c. 2170 BC) |

Saqqara |

102

|

0.1

|

| Neb-hepet-Re | 11th (c. 2130 BC) |

Deir el-Bahri |

70

|

-----

|

| Seankh-ka-Re | 11 th | Western Thebes |

Unfinished

|

|

| Ammenemes I | 12th (c. 1990 BC) |

Lisht |

296

|

1.3

|

| Sesostris I | 12th | Lisht |

352

|

2.3

|

| Ammenemes II | 12th | Dahshur |

263

|

1.8

|

| Sesostris II | 12th | Illahun |

347

|

2.9

|

| Sesostris III | 12th | Dahshur |

350

|

2.6

|

| Ammenemes III | 12th | Dahshur |

342

|

2.0

|

| Ammenemes III | 12th | Hawara |

334

|

2.0

|

| Khendjer | 13th (c. 1777 BC) |

Saqqara |

170

|

0.4

|

I do not include speculative reconstruction of unfinished projects, but I did assume a pyramid form for the tower-like structure at Meydum, although this structure may have been unfinished and is not excavated.

Important to our understanding of the Great Pyramid Project is the fact that burial mastabas continued to be built during the proposed era of the Great Pyramid construction of the IVth Kingdom. This implies that two social courses were being pursued, one for ordinary burials, and the other for the Great Pyramid ProjectCif the Great Pyramids were built during the IVth dynasty.

The outstanding size of the four Great Pyramids was one of the most glaring facts to strike my attention. Further, the four outrank all other projects in the cutting and placing of interior stones, not merely rubble. The techniques for cutting the exterior facing stones on Giza 1 are beyond our present grasp. As Petrie stated:

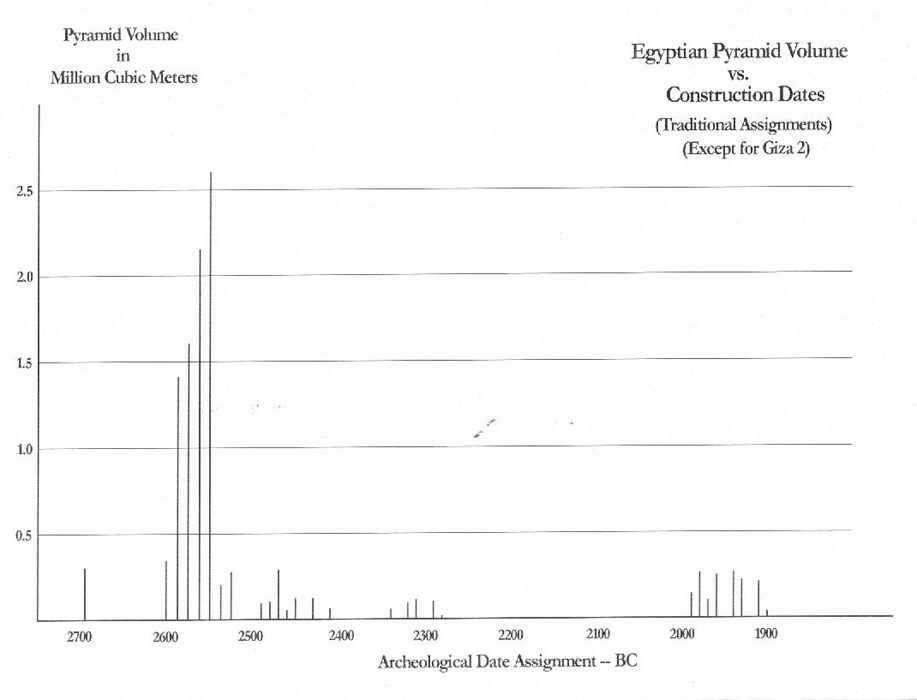

This difference becomes apparent if one

plots the pyramid volumes on a graph. The Figure is according to usual

archeological assignments and dates, except for Giza 2, which I shall explain.

(This plot includes only the most significant structures.)

|

From the volumes one can easily see that the Four Great Pyramids are in a class by themselves. The social resources and technical abilities to marshal such a project were truly phenomenal.

Many features of the four remain unexplained. These features include multiple chambers, peculiar arrangement of entrances and passages, passage slopes, chamber dimensions, stone course configurations, and so on. Refer to preceding and following Papers.

Other facts should be noted.

None of the four contained burial remains in historic times, although box-like coffers found in each of the two pyramids at Giza were suitable in size for human remains. Also, except for one unusual case, which I shall discuss below, the four were bereft on interior chamber and exterior surfaces of identifying marks, names, cartouches, or other means to place assignment. Not until two hundred years later did the kings begin to place religious texts on the interior walls.

The two great Daschur pyramids are assigned to one King, Seneferu, circa 2600 BC, simply because archeologists do not know how to fit them with the sequence of king reign's. The names of the kings are not all known with certainty; available records are faulty. Egyptian documents, dating many centuries after the IVth dynasty, claimed Seneferu built those two great structures but the difficulty is compounded because the tower-like structure at Meydum is also assigned to him.

Edwards, one of the most outspoken proponents for the evolutionary date assignments, admits that in spite of repeated attempts to make precise determination of dates and king reigns, the data are far from certain. He remarks that

ink inscriptions of this kind are sometimes misleading.In two books, The Monuments of Sneferu at Dahshur, Government Printing Office, Cairo, 1959, and The Pyramids, University of Chicago Press, 1961, Ahmed Fakhry goes to great lengths to show assignment of the Daschur pyramids to Seneferu, but with unconvincing evidence. He provides a photograph of the stone from the upper chamber of the Bent, but the supposed cartouche identifying Seneferu is painted on a coarse, unfinished surface and is not easily readable. It may be graffiti that someone placed there at a later time. And why bury it on the underside of a stone where it would not be visible to anyone?

Fakhry did much of the excavating work at Daschur, a project for the Egyptian Government that was never finished. >From the exterior temples he found much graffiti and other painted cartouches that showed Seneferu's identity.

This raises another specter. The exterior temples, causeways, small pyramids, mastabas and boat pits could have been placed there at times considerable different from the pyramid construction projects. Why would one build such huge gleaming beautiful mathematical monuments that could be seen from hundreds of miles away and then disarrange the site with uncomely mastabas and inferior imitations of that grand structure? I certainly would not want someone to clutter up my radiant beauty with such sorry distractions. Only cult minded people, longing to share in that glory, would cling to that shining memorial as their hope of entry into the mansion worlds on high. (See the Egyptian Book of Coming Forth Into Light, misnamed the Book of the Dead bymodern godless scholars, where the mansion worlds are listed, E. A. Wallis Budge, The British Museum, 1895.)

The assignment of Giza 2 to Khafre is based solely upon tradition and upon a statue found in an adjacent temple. Placement of that statue might have had nothing to do with the pyramid, or could have been Khafre's independent claim to the pyramid after construction.

Giza 1 has burial sites to the east and the west, including miniature pyramids, where the members of Khufu's family were interred. By tradition, the pyramid was his tomb. Except for a cartouche in the uppermost relieving chamber over the king's chamber, there is no hard evidence to confirm such tradition. This present study casts serious doubt that the four great structures was built as memorials to kings. Khufu may have claimed the pyramid for himself without knowing the mathematical intent of the designer/builder.

An unfortunate aspect of pyramid studies is the unwillingness of researchers to realistically evaluate the psychology of that great enterprise. The usual approach is to assume they were cult monuments, as a form of religious expression, without giving regard to their mathematical splendor. Such attitude then not only denies the mathematical design but refuses to consider it. Petrie's mention of the exterior mathematical slopes of 20-21 29 and 3-4-5 at Daschur and Giza was sloughed off; even he did not follow through on that crucial insight. Modern minds assume that if those structures were built as cult objects they would not be scientifically designed.

Our understanding and appreciation of those tremendous structures then is blunted and conditioned by our modern godless attitudes.

Mark Lehner goes through a heavy body of evidence to show how the ancient Egyptians were deeply involved with cult centers celebrating the after-life. The early sections of his book are titled: The Ka, the Ba, and the Body Embalmed C Burial Rituals of the Pyramid Complex C The World and the Netherworld C The Pyramid Texts (Book of the Dead) C and the Pyramid as Icon C before he gets to modern attempts to evaluate them scientifically. Then he intermixes nineteenth century religious interpretations with scientific views to further blunt the mathematical evidence. He especially is critical of Piazza Smyth, Astronomer Royal ofn Scotland, who truly had confused ideas, and then on to Petrie, who offered us such exquisite information. As Lehner states:

Lehner must avoid plain evidence that denies his godless concepts of human history.

Other problems beset the hypothetical sequence of construction. The sudden leap from mud mastabas to mountains of stone in less than one century has puzzled many people. Within the next hundred years the ancient Egyptians built the four greatest architectural structures in the world, and then spent the next thousand years in puny efforts to imitate that great feat C which came at the beginning.

Many observers have commented on the stupendous nature of the project C of only the Giza 1 project. Until late in the nineteenth century it was the tallest building in the world. It sat there in mighty splendor, as a monument to an intellectual and social presence upon this earth.

No wonder it entranced the generations.

Mark Lehner remarked on the magnitude of the task. He mentioned that in:

In attempts to assess dates for the Great Pyramid Project we must keep our viewpoints within reality. We cannot wrench the Great Structures into some unique stone-building prehistoric era, and then ignore the stone technology that built the many smaller structures that consumed more than a thousand years of Egyptian culture. If we did so we would invoke two stone-building eras, one prehistoric, and one within the historic memory of the early Egyptian dynasties C without any dynamic connection between the two.

The evolution of complex burial mastabas, when considered as a social phenomenon outside pyramid building, shows a progression from the days of the First Dynasty. Since they had advanced beyond mud bricks we must find the origin of the new stone methods. The stone mastabas of the Khufu-Khafre era show that those builders used technology similar to that developed for the Great Pyramids.

After two centuries of modern investigations along the Nile we can follow that evolution and the concept of pyramid design. Some great genius took the idea of mastabas beyond the common cultural mode. In the reign of Zoser of the 3rd dynasty he decided to add to a simple mastaba, in continuing steps, until he had built the first true pyramid, the Step Pyramid. Compared to later structures it was primitive in execution. Today it displays the evolution of thought and construction steps that led to its final form. But this is fortunate for us; we can now follow the gradual development into the four Great Structures. This evolution was documented by I. E. S. Edwards, in his chapters on the Step Pyramids and on The Transition to the True Pyramid. That documentation, later more explicitly defined by Lehner, helps us understand how the Egyptian culture developed until it could execute the Grand Design.

That genius not only was growing in his design finesse; he was also developing a culture that could provide social resources equal to that Grand Design.

He must have had tremendous persuasive powers. He did not get the support of the kings without magnificent intellect and personality. The kings must have fully believed in the enterprise; other wise they would not have provided the social support. In fact, the entire population may have had some understanding of the gigantic purpose, and willingly contributed to that amazing project. Perhaps they understood how those monuments would speak for untold millennia to their unique existence. They may have been convinced that no match to such an enterprise would ever again be attempted. They were right.

The only real question before is the time-frame necessary to accomplish that task.

Great Pyramid Stone Myths

We all know that the Great Pyramid at Giza contains 2.5 million stones. This number has been passed around, by the most elementary investigator, to the most sophisticated and expert researcher. One reads such remarks as, "Let us accept the reliably estimated figure of the pyramid containing 2.3 million blocks"

Mark Lehner, who works with both the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, and the Harvard Semitic Museum, in an interview with a PBS NOVA program, tried to demonstrate the amount of work involved in construction of the Great Pyramid. He said:

Unfortunately, Dr. Lehner glosses over quite a lot. Not only does he not want to deal with the accuracy of the joints; he also does not want to deal with the highly sophisticated stone drilling, lathing, and cutting equipment used by the ancient Egyptians to produce domestic artifacts, so refined and expert, that we today cannot duplicate those extraordinary feats.

Flinders Petrie, the outstanding surveyor of the Giza complex, noted many examples he found in his two seasons at Giza from 1880 to 1882. Refer to the illustrations in his Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh. Photographs of striking objects may be found at http://sunship.com/egypt/articles/.

Lehner's approach is what I call the wave-your-hand-at-it methodology. While I admire his great mind I also deplore his casual attitude that avoids the real challenges presented by the Pyramids.

When he experimented with quarry production rates using Egyptian men, he exclaimed how fast they could quarry stone. Unfortunately, they did not try to duplicate the ancient feat. He did not confine himself to copper tools, which supposedly those ancient people only knew. So he waved his hand again. As he said:

Later, on page 211 of his book, Lehner openly remarks that copper tools wider than 1/3 inch!! "simply will not work on stone." Whenever Lehner encounters unexplainable evidence he simply omits it from his book. Such practice is raw deception, violating intellectual integrity, in attempt to preserve his godless theories.

He also postulated that the gigantic granite slabs at Aswan were quarried with "pounders" of dolerite or other materials at least as hard as granite. He tried his hand at it. He took one of those "pounders" and beat on granite still sitting in the quarry. In five hours he was able to make a one-inch deep, one-foot square indentation. He noted that Ato be assigned to that task would be the grimmest of hells.@

He doesn't say how two-by-five inch slots were cut deep into the granite, as preparation for separating it from the mother rock. Those ancient people certainly did not do it with "pounders."

_Lehner clearly was concerned that his audience would not accept his attempt to duplicate those ancient quarry feats. By using a modern power winch he admitted that he could not reproduce the ancient methods. Instead of addressing the problem of the inadequate strength of copper he just added more men, and then waved his hand at it.

Peter Prevos also spent some labor in examining the engineering aspects of moving stones. But he also waved his hand at it. See his desk study at

http://www.qeocities.com/Athens/Oracle/2451/pyramid/desk.htm.

He also believed that "The production of the more than 2.5 million elements is the real achievement of the pyramid builders that built the great pyramid."

I didn't trust these wave-your-hand-at-it methodologies. Was 2.5 million a "well established" number? Or was it a mythical number? Lehner admits that the number of stones has never been rigorously examined.

If we compute the total volume of the pyramid, using Petrie's measurement of 755.73 feet per side, and 481.33 feet high, with the pyramid volume formula of 1/3 X base squared X height, we obtain more than 91,600,000 cubic feet. (2.6 X 106 cubic meters.)

Dividing the volume by the 2.5 million stones we obtain 36.64 cubic foot average per stone. This stone would measure 3.32 feet, 39.84 inches, or just about one meter on each side.

Simple observation shows that most of the stones are smaller than this. Only near the bottom of the pyramid are they such sizes. This larger size within easy visual sighting probably conditioned the estimate of 2.5 million stones.

As a first estimate of the actual number of stones, l took Petrie's scrupulous measurements up the four corners of the Great Pyramid. See Plate VIII appended to The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, First Edition, Field and Tuer, London, 1883. (The following editions do not have this appendix.) He listed them to tenths of an inch for the NE and SW corners, and graphed them for the other two corners. He measured 203 courses at 5451.8 inches height. While the course heights are irregular, with larger stones near the bottom of the pyramid, the average course height is 26.86 inches. This makes an average stone cube of 11.2 cubic feet, not 36.64. Then the total number of stones in the Great Pyramid would be more than 8 million!

This is quite a jump over 2.5 million.

Of course, most of the stones are not cubes. They are oblong objects. If we base our estimate on stones twice this size the number is still more than 4 million.

A stone the size of 22 cubic feet would weigh nearly two tons. The stones used in Lehner's methodology would weigh close to three tons. Many who watched the Nova program will quickly perceive the hand-waving methods Lehner used when he said the men could easily quarry stones weighing two to three tons. He slid over the problems of two or three men using unusable copper tools to cut the stone from the mother stone, and then maneuver them onto sleds, even though he claimed a small crew could easily pull the sleds. He said nothing about how those ancient Egyptians moved 55-ton granite blocks from Aswan, down the river on boats, up to the Giza plateau, and still further up to the King's chamber. (Petrie stated that the total ceiling weight was 400 tons with nine beams, page 80-81.) Did the ancient Egyptians have boats that could carry 55 tons? The boats that have been excavated adjacent to the Great Pyramid are much too puny for such a weighty task. They probably were intended only to take the king to heaven! Even the later Phoenicians (1500 years later) sailed the Mediterranean with boats that could barely carry 50 tons.

Still not satisfied, I took Petrie's measure of the joints of the descending and ascending passages. Perhaps they would tell us something of the size blocks used interior to the pyramid.

Unfortunately, the passages were carved out of large blocks of limestone set in place explicitly for the passages. They do not represent the core blocks. The average length of these large blocks is about four feet. For good photographs of the passages and chambers of the pyramid see

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/pyramid/explore/khufuenter.html

The stones were laid perpendicular to the slope of the passage floor. That is, they were laid such that they rested against one another, from the bedrock upward. Their angle is about 26.5 degrees, the same as the slope of the passage. The joints are not perpendicular to the earth's horizontal plane.

The roofs of the passages appear to be laid on top of these large passage side stones, again resting against one another from their start at bedrock. A seam is visible all along the top corners of the passages.

(The ascending passage was laid out similarly, but resting on core blocks.)

On the other hand, the average distance on the passage floor between joints is much less. This means that the floors of the passages were not part of the more massive blocks set in place for the walls and ceilings. If these distances represent stone courses, at a slope of 1:2, from Petrie's measurements the average thickness of the underlying courses would be about 20 inches, or one Egyptian cubit. (This implies that the joints represent horizontal breaks in the floor stone, not vertical breaks.) This value agrees with the mean value for the courses measured on the outside.

Another contribution to estimate of the number of stones can be obtained by the photographs displayed at

http://www.pbs.orq/wqbh/nova/pyramid/explore/khufutoplo.html

One can easily observe the remaining stone course sat the top of the pyramid. These photographs show that the top courses were leveled, and held to a constant thickness. The stones interior to a course were the same thickness as those that were on the outside edges of the course. We know from Petrie's measurements that the thickness of those top courses were about one cubit, or 20 inches. The stones are otherwise irregular in size, some measuring perhaps 30 by 40 inches in width and length. Some are more like cubes. Also, some appear to be contoured to one another. Many photographs and field drawings show contouring of stones to one another, not only for the lower courses of the Great Pyramid, but for other structures. This suggests that the builders were concerned about stress to the stones, and made them fit with one another on a wide scale, thus distributing mechanical forces. Like dominoes, the stones at the top of Giza 1 overlap one another from course to course, thus helping to distribute weight. This same method of weight distribution probably was used throughout the pyramid.

How much pressure could a block of limestone from the Giza Mokattam quarries be able to withstand before breaking or crushing? For example, if the stones were of unequal height in a course, or if the stones were cut unevenly in thickness, would the weight from overbearing courses cause them to be crushed? Would such forces cause instability in the structure? I can imagine cracks propagating if the forces were not evenly distributed. (The great fractures of the Bent pryamid might be due to uneven pressures within the structure, rather than from earthquakes.) From such reasoning one can safely deduce that the builders were careful to distribute the overlying weight. The easiest method was to make each course of constant thickness.

Following this trail of evidence I believe the number of stones in Giza 1 is more on the order of 4.0 million, not 2.5 million.

Clearly the rate of quarry, movement to site, placing and setting, is a more difficult task with a larger number of smaller stones.

The Rock Knoll

Another factor is the use of a rocky knoll around which the pyramid was built. The height of this knoll is uncertain but it would not impact significantly on estimates of the work involved in the construction.

Petrie gave the height of the entrance door at 668 inches, about 56 feet above the base. This is at the top of course #18. He then measured the distances down the passage slope to the lower chamber. He hit bed rock at 1340 inches. With a slope of 26.5° this would have been at a level about 70 inches above the outside base level, or about six feet. Therefore the knoll would have protruded into the structure only slightly above the first course.

The only other evidence for the size of the knoll could be obtained from an irregular shaft (well) cut from the bottom of the Grand Gallery to the subterranean passage, apparently for the escape of workmen in the lower chamber, or perhaps for later examination of the structure after substantial portions of the pyramid had been built. (By the time the builders reached the Grand Gallery the lower passages would have been closed up by the granite plugs sealing the ascending passage.) This well would show where the knoll begins at that location inside the pyramid, but the data are not published. Therefore, we do not know how much this knoll may have protruded upward at the center of the pyramid. Petrie did not believe it was great, showing on his cross-sectional sketch that it did not exceed the height of the intersection between the descending and ascending passages at 172 inches above the base. This would have been only the height of the first four stones courses.

Therefore the rocky knoll would have subtracted from the total work of stone quarry and placement by less than perhaps 5%.

The other notable feature of the rocky knoll was its blocking of triangulation for maintaining the square of the pyramid. Measurement methods had to work around that obstacle.

Rate of Movement

If we take the traditional assumption of twenty years for construction, we can calculate the rate of stone movement. The total mass would be on the order of eight million tons in 20 years. That is approximately 400,000 tons per year = 1100 tons per day, and in 12 daylight hours = 90 tons per hour. Or, if we grant only ten hours per day, as Lehner did in his assumptions, the rate would be 110 tons per hour.

Calculating from the number of stones at 4 X 106 divided by 20 years we obtain approximately 200,000 stones per year. This is equal to about 550 stones per day, 55 stones per hour, or 1.0 stone per minute. This rate was maintained for more than eighty years, from the structure at Meydum through the Mycerinus pyramid!

Logistics

If the stones were quarried at the average rate of 1.0 per minute, and if it took one half hour to quarry one stone, about 25 quarry crews were required. If it took a full hour to quarry one stone 50 quarry crews were required. If we assume open-face quarry, and that twenty feet of space were required for each crew, the distance required across the quarry open-face would be 1000 feet.

Lehner performed a thorough topological and historical survey of the Giza area. See his report, "The Development of the Giza Necropolis C the Khufu Project," in Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo, vol 41, p 109-143. He cited all significant exploration and research work in modern times. This report is invaluable for anyone attempting to understand the Giza area and the construction parameters.

Unfortunately, Lehner then proceeded to engage in highly speculative and questionable reconstruction of history. He repeatedly resorts to such phrases as "the ramps, or 'construction planes' are inspired by the remains of just such a construction embankment . . ." "construed," "could have been," and "might be." One of his most glaring analytical faults was total neglect of Giza 2, nearly the same mass as Giza 1. This neglect conditioned all of Lehner's subsequent attitudes about quarries and the work necessary for the Giza phenomenon.

He suggested that virtually all of the mass of Giza 1 originated in a quarry 300 to 600 meters directly south of the pyramid. According to his topological estimates the quarry basin measures 230 meters east-to-west at its widest point and 400 meters north-to-south, with 30 meter depth. He calculated that the total mass removed from the quarry would be about 2.7 million cubic meters of stone, neglecting loss due to cutting. This mass would meet the mass of stone required for Giza 1. He admits that these numbers are too neat. One cannot neglect quarry losses in cutting. Therefore, some material for Giza 1 must have been quarried elsewhere. (Again, he neglected to rigorously account for the source of Giza 2.)

We can see that 1000 feet, 330 meters of open face, might be available from that quarry.

Lehner then estimated the ramp which would be required to sled the stones up to the side of the pyramid. Putting aside for the moment the soundness of this proposal, we can use his numbers to estimate the ramp required from the quarry to the base of the pyramid. Evidence for a short ramp still exists north of the quarry leading to the pyramid plateau, composed of debris from the pyramid construction. Proceeding out of the quarry at 30 meters depth, and with a slope of 6.5°, (1/9), the length of the ramp would be 265 meters. This fits within the quarry, but would require that many stones be moved from the cutting location to the base of the ramp, a significant movement across the quarry floor in reverse direction.

Lehner apparently did not calculate the distances, for he shows many ramp fingers spreading throughout the quarry. They would have absorbed much of the quarry floor, and would not permit the slope requirements. This drawing is more Lehner propaganda.

The rate of movement up the quarry ramp to the pyramid would be determined by the need for supply, at one stone per minute. If the sleds were spaced thirty feet apart they would need to move at the rate of 30 feet per minute. This is about 1/3 miles per hour, and appears reasonable. Of course this velocity must be maintained for about 600 meters. The time over such path would be about one hour. The force required to drag the sled would be the vertical component of the weight up the ramp, plus the horizontal component due to drag. A three-ton stone would have a vertical component of 680 Ibs, plus 1800 lb horizontal if the drag coefficient were 0.3.

If one man could pull 60 Ibs, 40 men would be required on one sled. Thus we can see that the distance between sleds would be at least 80 feet plus sled length (four feet distance between men in double line).

This immediately creates a problem of sled rates. Now the speed to deliver one stone per minute becomes more than twice as fast, about one mile per hour, 90 feet per minute.

Clearly, if the drag coefficient were larger the number of men would increase, the distances between sleds would increase, and the rate of sled movement would increase for the same delivery rate.

Remember, this estimate is based on only one pyramid. Since Giza 2 is about 80% of the volume of Giza 1 this rate of production would be necessary every daylight hour, every day for 40 years! And we have not yet added the work at Daschur or Meydum.

Lehner specifically addresses the difficulty of locating quarries for Giza 1. As he said, " . . . no large quarry sufficient to the bulk of the Great Pryamid exists to the W, N, or E of the pyramid. " Hence there would be no such quarries for Giza 2. He could not identify a specific quarry area for Giza 2. He guessed at various locations. He believed the Giza 2 quarries were extended south of the Giza 2 pyramid, but then adds that, "Khafre must have quarried much stone to the E and N of his causeway (leading to the Nile) as well."

Thus we can see that Lehner did not clearly think out the sources and logistics of the problem of two large pyramids, limiting himself to Giza 1, and thus reducing our confidence in his estimates. He seized upon one quarry, which he believed was suitable in size and location for one pyramid, and then, once again, glossed over the remainder of this great enterprise.

We can see that the farther the quarries were from the pyramids the more men were required to keep up the rates.

The number of sled men from Lehner's scenario is the distance of travel divided by the distance between sleds. If the average distance on the quarry floor is about 100 meters to the foot of the ramp, 275 meters up the ramp, and another 400 meters to the pyramid as well as around the pyramid, the total distance in excess of 800 meters would require about 30 sled gangs in one direction, while others were hurrying back to pick up another load. This would be about 2500 men just or pulling sleds, day in and day out, for 40 years! Of course, we must add another 40 years for Daschur and Meydum.

Petrie noted that the limestone of Giza 2 was different from that of Giza 1:

Petrie remarked how he had walked extensively over the areas of the sites at Giza, Daschur, and Abu Sir without being able to locate limestone quarries. He speculated that the stones were carried from quarries at Tura and Massara across the Nile. Excavations over the past century have revealed some of the quarries, but solid information on the source of material for Giza 2, and the pyramids at Daschur is still lacking. We do know that the casing for Giza 1 came from Tura.

These facts further encumber the estimates of the labor and time needed for the construction projects.

Lift

After the stones arrived on site they had to be staged for lifting into place. Many different methods have been proposed, with no consensus among the many students of the pyramids. Lehner preferred a traditional ramp surrounding the pyramid. Remnants of small ramps have been found at various locations in the pyramid geographical areas. The location of the east and west cemeteries at Giza 1 would prohibit ramps built outward from the pyramid. Therefore, he elected for a winding ramp encircling the pyramid as it grew. But he admitted difficulties with such proposal. A ramp had two major problems. First, the amount of material required for a ramp is roughly the size of the pyramid. This would almost double the manpower required for construction. Second, how could the builders maintain alignment of the structure when it was buried under a mound of rubble? This is one of the most important elements in our understanding of lift methods. One cannot bury the pyramid inside a ramp and maintain a constant square, a constant slope, and the finesse of the slight indentation Petrie discovered at the center of the four sides of the core structure. (This indentation cannot be visually observed except from overhead aircraft with proper position of the sun.) As Petrie stated:

This hollowing is a striking feature; and beside the general curve of the face, each side has a sort of groove specially down the middle of the face, showing that there must have been a sudden increase of the casing thickness down the mid-line. The whole of the hollowing was estimated at 37 on the N. face; and adding this to the casing thickness at the corners, we have 70.7, which just agrees with the result from the top (71 +/- 5), and the remaining stones (62 +/- 8). The object of such an extra thickness down the mid-line of each face might be to put a specially fine line of casing, carefully adjusted to the required angle on each side; and then afterwards setting all the remainder by reference to that line and the base.

The reader can image what measurement task was required that each corner slope (42°), each side slope (52°), and each indentation slope had to be rigorously held to come together simultaneously at the apex of the pyramid. Not only did the slopes have to be maintained correctly, but perpendicularity with the ground had to be maintained to prevent skew. (A skew of one degree on the corners would have caused the corner to miss the apex by thirteen feet.) At the lower part of the pyramid the builders had no apex to orient against; they had to be able to project each of their alignments from the ground. They certainly did not hang a marker 480 feet in open air and then aim for it.

In discussion in his book Lehner believes these feats were accomplished by simple plumb bobs, set squares, and vertical plumb rods. Lehner apparently has never attempted a building of his own. He doesn't realize that such simple tools are not adequate to the refined geographical orientations and structural alignments found at Giza.

Whatever methods were used for lift, the faces of the pyramid had to remain open. The refinement of survey equipment necessary to accomplish such feats rivals anything we can do today. They certainly did not accomplish such tasks with plumb lines and water levels.

The difficulty may be estimated by the controversy surrounding Petrie=s original findings of geographical orientation of the Great Pyramid. Not satisfied that Petrie=s results were valid, various parties collaborated to have J. H. Cole attempt another survey. See Determination of the Exact Size and Orientation of the Great Pyramid at Giza, the Egyptian Government Press, Cairo, 1925. Cole=s results were slightly more variant than Petrie=s. But the small differences were only discernible with modern optical survey equipment. The contest arose over difference of less than two parts in 2300. This means that the original architect held the base lengths and orientations so close that today we debate their exact values. As Petrie stated, the difference around the perimeter of the Great Pyramid was no more than one could cover with one=s thumb. Such control was not done with primitive tools.

Following his usual methodology of waving his hand at insurmountable difficulties, Lehner ended with this remark: "The details of this must be left for a more lengthy discussion on this point."

If we assume that a mechanical lift of some design could perform the job we must give regard to the fact that one lift would not be able to handle a rate of 60 stones per hour. After the stones were in position at the lift they had to be moved onto the lift. Then the lift had to move them up to the next lift.

I thought I would consult a civil engineer who should know what he is talking about. As posted on his web site

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Oracle/2451/pyramid/desk.htm

Peter Prevos visualized the following:

Since Prevos did not know what he was talking about, I did my own calculation. I assumed the lift-men could pull 60 lbs. More than that would put a strain on them (day in and day out, ten hours a day, for eighty years!).

I calculated different leverage points

for a two-meter (six foot) lever. (Our calculations are limited by how far a

man's arms can reach to pull 60 Ibs.) I discovered that the amount of upward

lift was inversely proportional to the leverage.

| Leverage Ratio |

Amount of Lift Weight |

Vertical Lift Distance |

No. of men |

| 1:2 | 120 | 2 ft. | 50 |

| 1:5 | 300 | 1 ft. | 20 |

| 1:10 | 600 | 6 inches | 10 |

How would you locate 50 or 20 or 10 men around a 3-ft stone? By extending the sled? If each man required three feet of working space, paired on each side of the sled, 50 men would require 75 feet of sled; 20 men would require 30 feet; 10 men would require 15 feet. Then you would increase the sled length, the distance between sleds on the ramps, and increase the velocity proportionately to keep up the delivery rate.

Also, the distance on the side of the pyramid to obtain forward motion from lever crew to lever crew would quickly consume all available space. An 80-foot distance per drag crew would permit only 8 drag crews per side at the bottom of the pyramid, ever decreasing in number as the pyramid rose in height.

Still, more than one lift was required if the construction rates were to be maintained. These several horizontal lifts had to be placed around the perimeter of the pyramid, on successive courses. Meanwhile each lever position would require at least 20-ft distance into the side of the pyramid (6-ft levers on each side, plus sled width) to permit maneuvering.

As I thought about this scheme and estimated the space requirements I realized that simple lever systems would not work. I came to recognize that the builders did not construct pyramids by such methods. Or they had centuries to complete the task.

Peter Prevos may have convinced himself that levers could be used, but he will not convince any other thinking person. We now see why Lehner opted for a ramp.

Another scheme is ropes and pulleys. One can obtain considerable mechanical advantage with a few appropriately arranged pulleys. If the rope strength could handle three tons, one could arrange winches to create the lift. Then one could build a vertical slide that could be greased to reduce friction. (Animal tallow can reduce friction far better than water.) The slope of the pyramid at 52°would reduce the vertical component of the weight by 20%.

But we have no evidence that the ancient Egyptians knew ropes and pulleys. Lehner discovered mushroom-shaped stones with three grooves over the heads that could have been intended to accommodate ropes. He called them Aproto-pulleys@ but they offered no mechanical advantage except to guide thin ropes. (We also have no evidence of how they raised 55-ton blocks of granite 160 feet above ground.)

Since we do not know anything about the existence of such machinery we cannot judge the ability of this suggestion to perform the task.

From these estimates one can get some idea of the magnitude of the task C if the traditional views are correct.

In a brave effort to overcome the lift problem, Joseph Davidovits, wrote a series of papers, proposing that the limestone blocks were geopolymerized, meaning "cast concrete." He and Margaret Morris published a book entitled The Pyramids:An Enigma Resolved, 1988. This work caused quite a stir among geologists, egyptologists, and archeologists. After considerable study of pyramid rocks, and with lack of confirming evidence, including casting marks on the stones, this theory was rejected by most of the professional community. One need only look at the pyramids to see the great variety of natural stone cuttings. No two stones seem to be identical. If the Davidovits and Morris theory were correct many stones should be similar in size and shape. The evidence speaks contrary to this view; a million different molds would be required. This says nothing about where the slurry was mixed, how fast it could be poured, the setting time of the concrete, how they overlap one another like dominoes, and other factors. In her continuing struggle to support this theory Margie Morris talks about Asoft@ concrete that could be shaped to fit adjacent blocks, thus answering that question. Unfortunately, concrete does not become "soft." It becomes brittle, and would quickly flake and shatter during curing if forced to other shapes.

I think Margie molded too much pie dough to baking tins.

(Remember, we must maintain one stone a minute for eighty years!)

From such evaluation the theory of cast concrete seems utterly inane. It was an admirable attempt to solve the lift problem, but it failed. See a report in Concrete International, August 1991.

Given all these problems, it boggles the mind to believe the pyramids could be built in the time allotted.

Course Levels

Giza 1 and Giza 2 both display differences in thickness from course to course. From above discussion I showed why a constant thickness was maintained throughout each course. Not only were the thicknesses maintained constant, levels above base were also maintained.

The precision of stone cutting has been neglected in previous estimates of pyramid construction. From Petrie's excellent measurements we know the maximum difference in any one level for Giza 1 from the NE to SW corners. This is 5.2 inches near the bottom of the pyramid. Higher courses were maintained much closer. The mean difference in levels over 200 courses was 1.3 inches. About 95% of the courses were held within 1.6 inches of level variation from corner to corner.

To repeat once again, one does not obtain such control through primitive tools.

The maximum difference in thickness from corner to corner for any one course is 4.9 inches, with a mean difference over 200 courses of 0.8 inches.

If different courses were simultaneously laid at different levels over the spread of the pyramid during construction, the ability to measure levels and thicknesses would have been hampered. Visual sighting could not be made. The levels and thickness could then only be maintained by measuring each stone for thickness as the layers proceeded upward. Statistically this would have produced thickness and level variations far greater than those actually built. Lehner argued that statistical variation would cause smaller as well as larger differences in level and thickness, and thus would compensate as the structure rose higher. But this fails to consider the clearly intentional design variations from course to course, and how closely they were held.

Hence, the stones must have been cut to specified size at the quarry. The time required to prepare each stone was more than merely cutting them loose from the limestone bed. If the stone dimensions had varied beyond specified tolerance the builders would have had an impossible task of selecting stones to hold the courses to the small variation we now observe. They had to use the stones as they came from the quarry, without taking the time to measure and select. If not, then the task of cutting them to such precision had to be done on site, further encumbering site activity. No civil engineer, given the magnitude of the task, would have chosen that sequence.

If the stones were trimmed on the structure it would contain the debris of such trimming, and might have caused the stones to shift apart with repetitive treading by the workmen, thus destroying the integrity of the course. Simple borings from some of the passages within Giza 1 have shown sand and limestone chips between stones, but the amount of such extraneous material has not been analyzed or published, as far as I know.

Petrie was aware of this problem. In a proposal by J. Tarrell, and written by Petrie, they discussed how these stones might have been created and sorted.

Clearly, the technical specifications of the project affect all elements of design and logistics. Again, as far as I am aware, no one has incorporated calculations of this unique process control in estimates of the time for construction. Of course we can take Lehner=s attitude that cult minded people do not engage in such strange practices.

Sequence of Construction

In a paper entitled AA Reconciliation of the Geological and Archaeological Evidence for the Age of the Sphinx and a Revised Sequence of Development for the Giza Necropolis,@Colin D. Reader explored the contradictions between the accepted construction chronology, and the archeological evidence. I offer his remarks in detail because they nicely describe the problem. He was following discussions initiated by Robert Schoch, who has been researching the age of the Great Sphinx. From water erosion Schoch proposed that the Sphinx long predates the arid conditions during the supposed IVth dynasty pyramid constructions, to a time when Egypt saw considerable rainfall and water erosion. Refer to Schoch's Voices of the Rocks, Harmony House, 1999.

Reader said:

The eastern end of the causeway runs along the top of the southern Sphinx exposure and, when viewed in plan, it can be seen that these two features share a common alignment. Experience suggests that such common alignments rarely develop by chance and this raises the possibility that the two features were constructed at the same time. It follows, therefore, that if the Sphinx pre-dates Khufu, the causeway must also have been constructed some time before Khufu's development of the site.

Further support for this hypothesis is available from analysis of the spatial relationship between the causeway and the two quarries that were worked during Khufu's reign. With respect to the southern most of these quarries, Lehner states that AAt the N. the floor of the quarry appears to slope up to the Khafre causeway . . . Later, when discussing the northern quarry, A[the area] contained dumped debris which apparently fills an extensive quarry limited on the S by the Khafre causeway and on the east by the Sphinx depression.@

Under the conventional sequence of development, "Khafre's" causeway (and the Sphinx), were undeveloped at the time of Khufu's quarrying. If this sequence is correct, why should the extent of the quarrying have been limited by a feature (the causeway) that was not developed until sometime after Khufu's reign? The conventional sequence of development requires us to accept that Khufu's workmen went to the trouble of opening up a second quarry to the south of the causeway, rather than remove a linear body of rock which, at the time, served no apparent purpose.

The common alignment of the causeway and the southern Sphinx exposure indicates that, like the excavation of the Sphinx and the construction of the Sphinx temple, the alignment of "Khafre's" causeway was established some time before the construction of Khufu's mortuary complex. Under this revised sequence of development, interpretation of the spatial relationship between the causeway and Khufu's quarries becomes quite straightforward - with the causeway limiting the extent of the later quarrying works.

This respect for an earlier causeway also shows that it must have been held in high esteem. Otherwise, the quarry men would just simply have worked through it and destroyed it.

Reader seems to have drawn a false conclusion. The coincidental alignment between the Khafre causeway and the Sphinx pit need not have been directly related. The builders of the causeway may have merely followed the easiest path to the Nile without violating the Sphinx integrity. The important point is that the traditional Giza 1 chronology is false.

As I shall show, other evidence points to Giza 2 as built before Giza 1.

Radio-Carbon Dates

Lehner took organic samples from the pyramids of Senwosret II near Meydum, and from Sahure at Abu Sir. He had these radio-carbon dated. To his surprise the average date for the Old Kingdom at Abu Sir made the pyramids 350 years older than the accepted chronologies. He then took many other samples from other sites, but the results of those tests have not yet been published, April, 2001.

Previous radio-carbon dating had been done on objects that had been moved from their context C mummies, wooden boats, and so on. This resulted in contamination of the samples, with unreliable results. Unfortunately, Lehner makes the assumption that the Great Pyramids were built during the Old Kingdom. We don't know this, they might be far older. Second, he has not used samples from those sites. Wooden beams exist as part of the structure inside the Bent Pyramid but the Egyptian government may prohibit removing specimens from those beams.

Hence, we have no reliable radio-carbon dating of the Great Pyramids.

Weather

As Petrie stated:

. . . In Greek times the rain appears to have been just as rare as now, or even rarer in Upper Egypt.

. . . Again it may be observed that neither rain, nor any sign of rain, is shown in the paintings of the tombs; no wide hats, no umbrellas, no dripping cattle, are ever represented. Mud-brick tombs, covered with stucco, still remain from the third or fourth dynasty, when they were built without an apparent fear of their dissolution.

. . . The general condition as to the climate, then, seems to be that there has been no appreciable change in rain-fall, river flow, or sand-blow during historic times.

. . . Underneath the sand in the eastern part of the site is a compact surface of gray alluvial soil. The "mud mass," as we call it, resulted from the purposeful toppling of mudbrick walls by those who abandoned the site, after they had removed everything of value, such as wooden columns and even mudbricks, from the massive walls. If the occupants had abandoned the site gradually and left the walls to collapse over time, we would expect to find a pattern of sand layers intercalated with toppled or deteriorated mudbrick. We have watched sand accumulate over the floors of our excavated squares within weeks or even days and seen sandstorms leave a foot of sand banked up in our trenches; yet none of our sections showed much sand. The tumbled mudbrick lies directly on the ancient floors or upon the ancient refuse lying on the floors, suggesting that the walls were toppled suddenly.

. . . All the evidenceCpottery, seal impressions, and stratigraphyCindicates that this demolition took place at the end of the Fourth Dynasty. The forces of erosion subsequently removed a good part of the tumbled ruins of the mound, leaving walls ankle- to waist-high embedded in compact mudbrick tumble. However, thanks to these processes, we can discern the outlines of major walls with only shallow excavation through the mud mass. In many squares we can discern the lines of walls by lightly scraping or even brushing the surface with our trowels. The walls are often revealed by marl lines that result from the plastering of desert clay, or tafla, on their faces.

Here Lehner diverts attention away from the fact that the bottom-most layers of his excavation show lack of blowing sand. Those village structures had to be built when no sand was moving across the Giza plateau. This condition could exist only if something was holding back the sand C a surface covered with vegetation C grasses, trees, and plants.

Furthermore, the walls were toppled suddenly to level the site, with all artifacts taken away, because that period of construction had ended and the site was not longer used for habitation or work.

This evidence suggests that the Great Pyramid construction period was at a time when sand was not blowing across the Giza plateau, prior to the Old Kingdom. Or somehow, human activity on a massive scale was taking place not connected with the pyramid construction. But such thought seems self-contradictory.

The evidence also suggests that after the massive activity was complete the site was abandoned.

If we follow this suggestion we are forced back to the previous contradiction, that the stone technology of the later Old Kingdom was somehow developed independently of the earlier pyramid activity.

At this point it may be helpful to note that Egyptian chronologies have been subject to debate for centuries. Some persons still cling to the notion that Egyptian history actually is a thousand years older than current estimates. This seems to be supported by Lehner=s radio-carbon dates. When samples become contaminated the measured dates always come closer to us in time. Then Lehner=s reported dates might even be earlier than 350 years from present chronologies.

Even so, a thousand years would not be sufficient to capture an ecological milieu with rain.

Clearly, we are up against conflicting evidence. We simply do not have sufficient data to come to hard conclusions.

One of the Greatest Objections to Accepted Chronology

Petrie offered one of the most serious objections to the traditional chronology and assignments to the IVth dynasty kings.

(1) How does it happen that the Pyramids are of such different sizes? The theory of accretion answers that each king continued building his Pyramid until his death, and hence the Pyramids differ in size because the reigns differed in length. When, however, we see that the lengths of the reigns are not in proportion to the bulk of the respective Pyramids, this apparent explanation merely resolves itself into saying, that because two quantities vary they must be connected. On comparing the lengths of the reigns with the sizes of those Pyramids whose builders we know, the disproportion is such that Khufu, for instance, must have built the Great Pyramid 15 times as fast as Raenuser built the Middle Pyramid of Abusir; or else Raenuser built for only 1/15th of his reign; either alternative prevents any conclusion being drawn as to inequalities in time producing inequalities in the sizes of the Pyramids.

(2) How could later kings be content with smaller Pyramids after Khufu and Khafra had built the two largest? This question the accretion theory cannot explain; for many of the later kings lived nearly as long as Khufu and Khafra (one even much longer), without producing anything comparable in size. When we look at the mournful declension in the designs of Pyramid building, from the beauty of the fourth down to the rubble and mud of the sixth dynasty, the falling off in size as well as quality is merely part of the same failure.

(3) How is the fact to be accounted for that an unfinished Pyramid is never met with? In the same work in which this question is asked, it is said of one of the Abusir Pyramids, that it "seems never to have been completed;" and of the South Stone Pyramid of Dahshur, "The whole pyramid was probably intended to have the same slope as the apex, but the lower part was never completed." This question is only another form of No. 5.

(4) How could Khufu have known that his reign would be long enough to enable him to carry out such a vast design? However this may be, he certainly worked far more quickly than any other king, and the arrangement of the interior of his Pyramid, as we shall see below, proves that it was all, or nearly all, designed at first.

(5) If a builder of a great pyramid had died early, how could his successor have finished the work, and built his own pyramid at the same time? First, we have no proof that a successor did not appropriate the work to himself, or share it with the founder; and, secondly, no other kings worked at a half, or perhaps a tenth, of the rate that Khufu and Khafra worked, or with anything like the same fineness; and hence any king might easily have had two pyramids on hand at once, his father's and his own.

The accretion theory, then, though not actually condemned by the application of these questions which are adduced in its support, is at least far from being the "one entirely satisfactory answer" to them, as it has been claimed to be. And the supposed proof of it, from the successive coats of the Mastaba Pyramids of Medum and Sakkara, is, in the first place, brought from works that are not true Pyramids; and, in the second place, shows that the buildings quoted were completely finished and cased many times over, probably by successive kings, and not merely accreted in the rough, until the final casing was applied. A confirmation claimed for this theory is "the ascertained fact that the more nearly the interior of the pyramid is approached, the more careful does the construction become, while the outer crusts are more and more roughly and hastily executed." This is certainly not true in many, perhaps most, cases. The Pyramids of Sakkara, as far as they have been opened, show quite as fine work in the outer casing as anywhere else; and the rubble of the inside is equally bad throughout. The Great Pyramid of Gizeh shows far finer work in the outermost parts of the passage, casing, and pavement, than in most, or perhaps all, of the inside, and the Second Pyramid is similar. In a great part of the pyramids we know nothing of the comparative excellence of the work of different parts, comparing fine work with fine work, and core with core masonry.

This absurd proposal is more easily understood for the Seneferu project of Meydum and the two Daschur pyramids. His total construction volume is 3.5 million cubic meters of stone, or about 10 million tons of stone, 30% more than the volume of Giza 1, and more than one-third of the IVth dynasty social investment, without any consideration of why he would build himself three pyramids, two of giant order. If he also miraculously completed his three pyramids before he died, he was able to do it in 24 years, the length of his reign from 2575-2551 BC, according to the dates published by Lehner. Khufu then comes along and spends 30% less in social resources in 23 years, and we give him all of our attention.

As my previous analyses show, all four Great Pyramids were part, of one vast construction project. That project was carried on linearly until the last Great pyramid was built, and could not have been associated in any way with reigning kings. If we are willing to swallow all the logistical and mechanical difficulties I outlined above, to make the construction cover 100 years of time according to traditional spans, then some person or some segment of the population was able to not only conceive of the project, but also to execute it. Either this meant that a continuity of concept was maintained between generations, with full knowledge of design and methods of execution, or the genius behind the design lived an extraordinarily long life.

General Remarks

If the traditional evolutionary chronologies are at fault we could come to better grasp of the projects with considerable more intellectual integrity.

Petrie emphasized the many outstanding features of the four Great Pyramids. When summarizing his measurements he made numerous remarks noting the excellent workmanship of the four large structures in contrast to other works. In reference to the pyramid of Mycerinuis, the third smaller pyramid usually associated with the two large structures at Giza, he said:

Furthermore, the chambers of the Mycerinus pyramid are irregular in construction, apparently the result of several design changes.

From the details of his measurements Petrie concluded that this third pyramid was originally started no larger than some of the small pyramids on the same hill, but that the builders, for some reason, enlarged the pyramid before it was encased, and deepened the first chamber, adding a second chamber as part of the second design. The chambers do not follow clean geometric design as do the chambers of the large pyramids.

The four large pyramids were well planned; they do not exhibit changes during construction. Although arguments have been presented to show that the Great Pyramid builders changed their minds during construction, these arguments are easily refuted, as Petrie was careful to do. Only less knowledgeable individuals retain such beliefs. My mathematical analyses show how erroneous such notions are.

From Petrie's measurement of the geographical orientations of the several pyramids he concluded that the third and lesser pyramids of Giza were so inferior in workmanship that they ought not to interfere with the determination of the north pole position from Giza I and Giza 2. Again, an item adds to our list to show that other structures are outside the provenance of the four Great Pyramids.

He also surveyed the temples of the Giza complexes. In one temple he found the workmanship not at all equal to the Great Pyramid. The walls were far from vertical, or square with each other in plan and that the irregularity of the walls discouraged me from using polestar observations for it.

(When Petrie wrote in 1882-1883 a general expectation existed that the pyramids were built so precisely they might offer information on planetary pole drifts.)

In contrast, Giza I has orientation and workmanship that matches the ability of modern engineering.

Petrie also surveyed the small pyramids of the sixth dynasty at Saqqara, including that of Pepe II. He reported that the general bulk of this pyramid is of very poor work; merely retaining walls of rough broken stones, filed with loose rubble shot in. This appears to be the usual construction of the sixth dynasty.

The sixth dynasty was circa 2300 BC, some three hundred years after the assigned dates for the four great pyramids.

Petrie commented on the equal quality of the Giza and Dashur great structures:

Petrie carefully differentiated between the four Great Pyramids and all others. Of the several categories

We can look at this another way.

If we were to remove the four large structures from the above Figure we would more easily recognize the abilities of ordinary mortals by the size, (as well as quality), of the remaining structures.

The four Great Pyramids exhibit design, execution, and marshaling of social resources that exceed ordinary mortals.

Those pyramids were not built from primitive desires for cult monuments to immortality. Those pyramids represent monuments to a class of people, decipherable only by minds equal to theirs. They merely used the kings as a vehicle to accomplish their objectives. Then the kings, believing the individuals structures were intended for them, claimed them as their own.

Petrie made a number of other observations that help us decide the sequence of construction, based on the evidence and not upon tradition.

The North Pyramid at Dahshur is about equal in general masonry to the Second of Gizeh; but inferior in the accuracy of its internal work. It is most of all like the Great Pyramid of Gizeh in its style of work, the fineness and whiteness of its casing, and the design of the overlapping (interior chamber) roofs; but it is inferior to that Pyramid in every detail.

The SouthCor bluntedCPyramid at Dahshur is of good work; very good in the lower part of the core, but poorer in the upper parts, both in quality and working of the stones. There is, however, some very good work in the joints of the casing of it; flaws in the stone have been cut out, and filled in with sound pieces. It is only inferior to the preceding in the quality of the casing. The general impression received, from the work and design of these two large Pyramids of Dahshur, is that they are more archaic than the Great Pyramid of Gizeh: and the builders seem to be feeling their way, rather than falling off in copying existing models.

Petrie went on to remark about the Meydum pyramid.

The Mastaba-Pyramid at Sakkara (or Great Step-Pyramid) is built of bad and small stones, often crumbling to dust: its casings are fairly good, though of small stones as they vary in angle, no accuracy seems to have been aimed at.

Some persons debate the structure at Meydum. Was it completed, and then later scavenged to make use of its stone? The existence of intact casing around its base suggests so. But why would anyone go to the trouble of simply dismantling it, when other structures remained intact until more recent centuries? It seems to me that the ancients had a great respect and awe for those projects. More recent men do not.

As Lehner pointed out, even the small pyramid of Mycerinus withstood an assault to dismantle it. The larger pyramid at Meydum would have been even more impervious to such assault. >From this evidence we are strongly inclined to concluse that it was left in an unfinished state.

The step pyramid of Zoser had five distinct changes in design, progressing from the first simple stone mastaba to successive enlargements until the final step shape. It demonstrates changes in concept as it was progressively enlarged. One receives the impression that a learning period was underway during its successive stages.

Various scholars attempt to diminish the significance of this sudden evolution. Although decorative panels of stone are contained within contemporary mastabas one cannot survey the extensive complex of Zoser, with its ornate decoration, together with the step pyramid, and not recognize the immense leap in technical innovation it represents. One can also see the initiation of social resources dedicated to stone monuments. The huge wall of carefully cut stone that once surrounded the complex is almost a mile in length.

During the reign of King Zoser, Imhotep is accepted as the center of those developments. Therefore it would not be unreasonable to suggest that Imhotep was the designer of the Great Pyramid program. If so he must have been an old man when it was begun, (or he had extra long life). If Imhotep was not alive during the implementation of that program he either had to teach his knowledge to native Egyptians, or there were other members of his culture who carried on after him. These, then, as Petrie said, would be a few men far above their fellows, whose every touch was a triumph." Only Imhotep has come down to us through tradition and statuary evidence.

From this brief review it appears that the sequence of stone pyramids proceeded from the first initial concepts at Saqqara, with its successive layers approaching a true pyramid shape. The designer-builders then went to Meydum, where they further developed their concepts and construction techniques. Perhaps a few abortive efforts lay between, but thereafter they quickly started the vast project of the four Great Pyramids.

From other evidence I shall show that both the Meydum and the Mycerinus pyramids served as a terminus a quo and a terminus ad quem to define the era of this immense project. Both exhibit refinements in abilities that approach the Four, but both were left in an incomplete state.

Later, the Mycerinus pyramid was adopted by that king, and used as his grasp for immortality.

We can now better understand the difficulties we have with that ancient phenomenon. If the evolution from the Zoser step pyramid represents a learning process in handling stone, as also shows in the improvement in layering at Daschur and Giza, we would have one continuous program to reach the ultimate in the Great Pyramid. Certainly, the Egyptian social techniques of stone were developed during a continuous period. But did that period evolve during the reigns of the kings we traditionally accept, or did those kings merely appropriate those structures for their private immortality? Is it possible Zoser built his complex around a preexisting structure? Did Menkaure grab the only worthy remaining site at Giza, following in his fathers footsteps, and appropriate that pyramid as his own, adding to it and making changes according to his personal desires? Did Khufu and Khafre build their personal monuments and family burial grounds in the shadow of huge structures which stood long before they were born? Did this stone technology, certainly impressed upon generations of quarrymen, craftsmen, designers, and project engineers, then carry down to the traditional king reigns, only to slowly deteriorate with succeeding generations?

The dates of the kings are still subject to debate. Edwards and Lehner differ as much as forty years in the reigns. If the radio-carbon dates are suggestive, the onset of stone technology might be several hundred years earlier than now understood. This would give more time for construction, and also show why the kings of the IVth dynasty could appropriate monuments that were not originally intended for them.

The Khufu Cartouche

In preceding discussion I briefly indicated the evidence that traditionalists use to tie the Daschur pyramids to Seneferu. We must give regard to the fact of considerable graffiti found on building blocks at all sites. Quarrymen were not loathe to inscribe blocks of stone.

When Howard Vyse blasted his way into the chambers located directly above the King=s Chamber in Giza 1 he discovered samples of this graffiti. But he also made an important discovery: a cartouche showing the name Khufu was on the ceiling of the top-most chamber.

Without question this would identify Giza 1 as belonging to Khufu.

But why Khufu would stick his name on the ceiling of a chamber to which there was no access, and which would be read by no one as long as the pyramid stood intact.

If I were a king and wanted to identify my property I certainly would not do so in a manner that would never be seen.

It just seems so convenient as a modern forgery to prove identity.

The same objection exists for the Seneferu cartouche found on the underside of a floor block in the upper chamber at Dashur.

What was going on with these kings, and the means they used to identify themselves?

Or did the kings know nothing about those strange methods?

The peculiar nature of these markings caused Zecharia Sitchin to propose that Vyse created a forgery. If Vyse did so he would have had to place it an area not previously known by many travelers. Thus he chose the remote inaccessible chamber.

But why would Vyse create a forgery merely to Aprove@ that the pyramid belonged to Khufu?

A thorough discussion of this problem was presented by Martin Stower. See

http://martins.castlelink.co.uk/pyramid/forgery

Stower rejected the theory that Vyse created a forgery.

One can invent scenarios for this strange behavior.

Perhaps Imhotep had an agreement with the kings that no visible markings of any kind appear on the pyramids of his Grand Design. He may have been forced to this position because the completion dates could not be predicted beforehand and hence could not be assigned to any king. Also, he may have desired to leave them unmarred by graffiti. When the structures were completed Imhotep may have promised the respective kings that he would give that structure to the reigning king. After all, they had supplied the social resources. Thus the Bent pyramid was completed during the reign of Seneferu, and Giza 1 was completed during the reign of Khufu. Then ownership became part of that king=s memory, as has come down to us through the millennia. To satisfy the respective king Imhotep placed a symbol of the ownerships as a token to that king, but where it would not mar the appearance.

Of course, we shall never really know.

Our Lack of Knowledge

Our lack of knowledge shows in several crucial areas:

We don't know how they were able to:

1. make artifacts of such refinement and

finesse we today cannot repeat,

2. quarry and finish hard granite,

3. move 55-ton stones down the Nile and up to the pyramids,

4. quarry, move, and set stone at the rates necessary to complete those

projects,

5. lift stones into place on the structure,

6. measure and hold alignments up the sides and corners of the pyramids that

would hold true positions, or

7. orient the structures to geographical true positions that test our modern

survey techniques.

Whatever technology or machines may have been used to accomplish these extraordinary feats none of it has remained as evidence. This is the reason Lehner must theorize that they used primitive methods. This barrier to clean understanding is reinforced by the fact that the technology was fairly widespread, as witnessed by scattered artifacts. How could those ancient people produce such works and not leave tell-tale evidence?

One suggestion is that the secrets were held by a small group of experts, remembered by us as a Apriesthood.@ The workers were under severe penalty of death if they dared to reproduce or carry away any such machinery. Then the Apriesthood@ destroyed those machines, and hence we have no evidence.

But such suggestion is so far-fetched it

is hardly credible.