Evidence

of Advanced Machining In Ancient

Stephen

S. Mehler, MA

The idea

that some form of advanced machining technique was utilized by the ancient

Egyptians is

one that has been circulating in the literature for well over ten years.

I have presented the concept in my two books, The Land of Osiris (Adventures Unlimited Press, 2001) and From

Light Into Darkness (Adventures Unlimited Press, 2005).

The idea has been popularized and was presented to me in 1996 by

engineer and master craftsman Christopher Dunn and detailed in his landmark

book, The Giza Power Plant (Bear

& Company, 1998).

Over the

intervening years, both Dunn and I have undertaken many trips to

pounders

and hammers. Dunn reported in his

book, and continues to find, examples of multiple contoured angles, perfectly

square corners and smoothly polished surfaces, and tolerances over 1/10,000 of

an inch in the hardest stones known.

In my

first book, I presented the concept that a series of sites known today as

Dahshur, Sakkara, Abusir and Abu Ghurob, Zayiet el Aryan, Giza and Abu Roash

were once interconnected and known as Bu

Wizzer—The Land Of Osiris—and all featured stone masonry pyramids and

temples and were linked together as an ancient power grid constructed over

10,000 years ago. The ancient

stone masonry pyramids were never originally designed and built to be tombs

for kings, or anyone, but as energy devices that utilized flowing water and

solar power from sunlight to produce varied forms of energy for the use of all

people. These ancients whom we

call Khemitians, not Egyptians, but

who were indigenous ancient Africans, employed advanced forms of engineering

and manufacturing to produce the artifacts in stone—and to cut, shape and

lift the thousands of tons of stone that we see remnants of today.

A recent

tour and research trip that I led to

Two

sites that I discuss in detail in my first book are that of Abusir and Abu

Ghurob, located some two kilometers south of

About a

½ mile east of Abut Ghurob is the connected site of Abusir.

There are many amazing artifacts and partial structures still to be

found here. I recently found an

example of two ancient holes drilled into a basalt slab (Fig. 5).

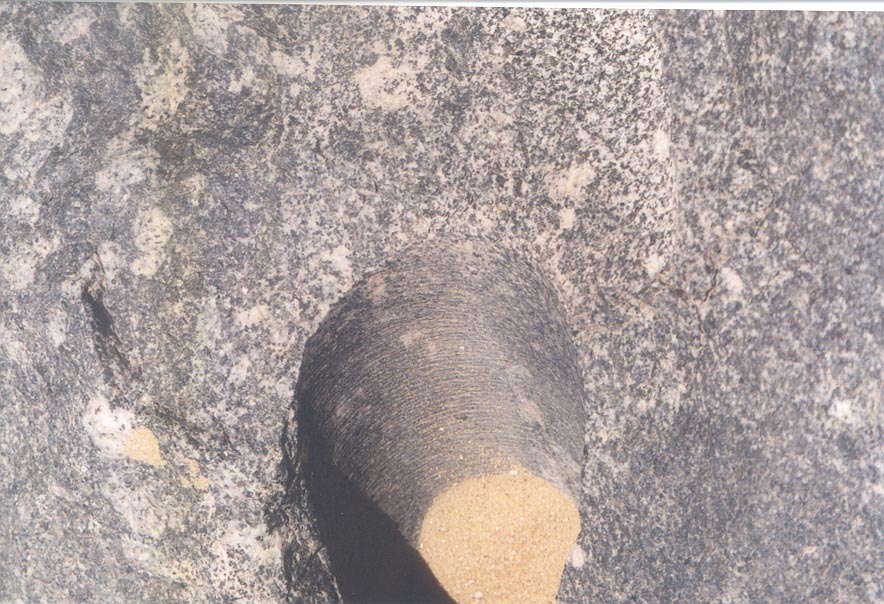

A close-up photo of the bottom hole (Fig. 6) possibly shows spiral

groove marks cut into the stone when it was drilled.

I showed this photo to Chris Dunn and he responded by sending a

close-up hi resolution photo of his own (Fig. 7).

Dunn took this photo of a circular hole found in the granite of the “

Other

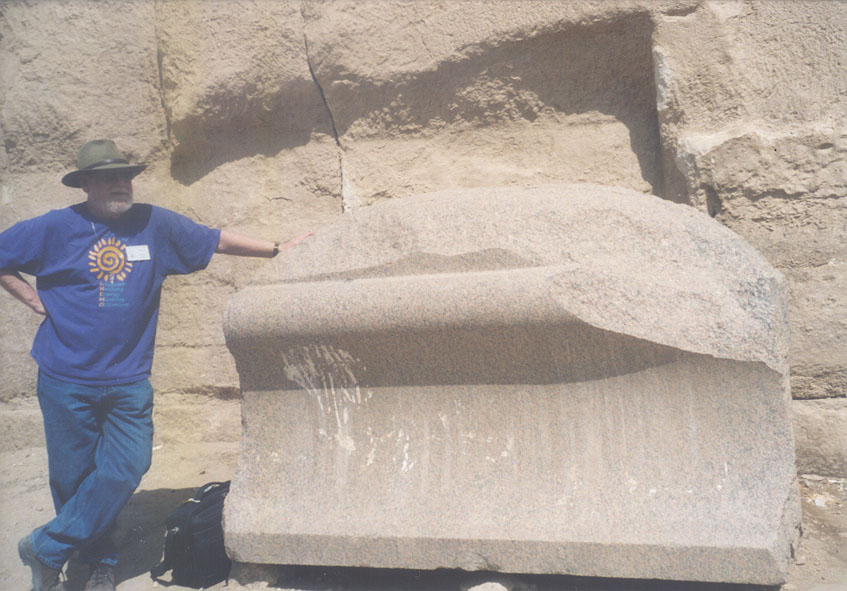

evidence we have studied over the years include the famous stone box found in

the King’s Chamber (sic) of the Great Pyramid.

Erroneously labeled as a “sarcophagus,” although no body or

evidence of burial has ever been found in the chamber, the box is made of

On the

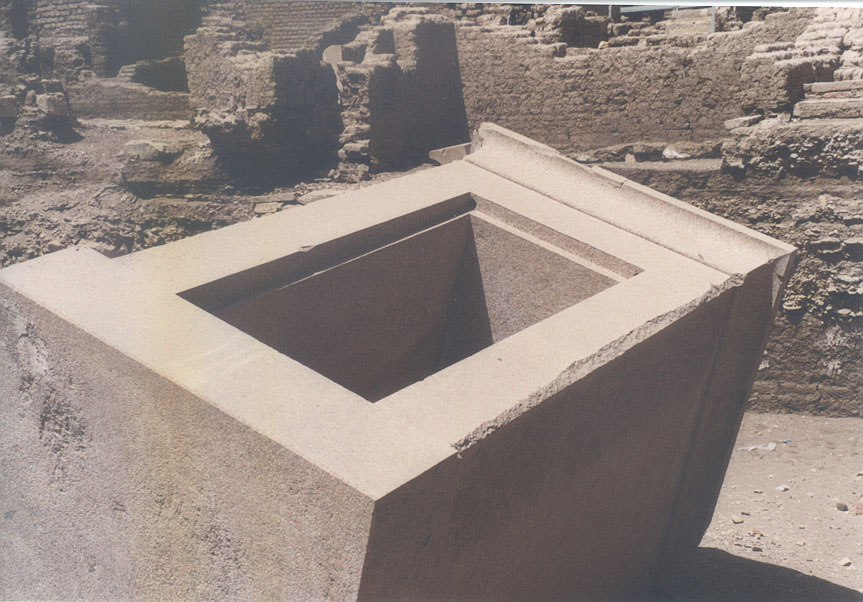

At the

site of Sakkara, some 10 kilometers south of

As we

continue to gather and direct an interdisciplinary and holistic research

effort in this area, with varied engineers, physicists, chemists, geologists,

and archaeologists not bound by the outdated and incorrect paradigms of

academic Egyptology, we will be able to present all this evidence that an

advanced indigenous civilization once existed where Egypt is today—a culture

capable of cutting, shaping, lifting and placing in precise geometrical

arrangement, the hardest of stone found on our planet, utilizing highly

sophisticated and technically superior methods and procedures.

I urge anyone interested in this line of research to come to

Figures

for Advanced Machining Article

Fig.

1—

Fig.

2—Abu Ghurob. Altar carved from alabaster.

Photo by author. 1997.

Fig.

3—Abu Ghurob. Alabaster “basin” with round hole drilled through stone.

Photo by author. 2007.

Fig.

4—Abu Ghurob. Two holes drilled

into alabaster stone. Photo by author. 2007.

Fig.

5—Abusir. Two holes drilled into

basalt stone. Photo by author.

2007.

Fig.

6—Abusir. Close-up of drill hole

in basalt with possible spiral grooves. Photo by author. 2007.

Fig.

7—

Fig.

8—Abusir, Remnant of granite pillar. Photo

by author. 2007.

Fig.

9—

Fig.

10—

Fig.

11—